You must be wondering about this title and what those three could have in common: Freud, the father of psychoanalysis; an illegal hard drug that has caused death and destruction to many; and a medical intervention that changed how medicine, especially minor surgical procedures, is performed.

Sigmund Freud was born in 1859, an intellectual colossus, a clever neurologist, an inquisitive scientist, and a solver of problems that plagued the human mind. He was as controversial as he was brilliant.

In the 1880s, he was living in Vienna, where he had studied and qualified as a medical doctor at the University of Vienna. He was a talented scientist with ambitious goals, eager to discover the next groundbreaking discovery that would establish him as a leading figure in the scientific world. He dabbled in various fields, including physiology, dermatology, and neurology, before settling into psychiatry, to which he would dedicate the rest of his life.

At around the same time, a popular drink was making the rounds across Europe, known as Vin Mariani. This was the innovation of Alberto Mariani, a French entrepreneur who, having heard of the purported properties of the coca leaf following the Spanish invasion of South America, began importing the leaf to Europe. He steeped the leaves in French wine, producing a much-touted drink said to revitalize its users.

This was the precursor to French wine coca in America and, subsequently, Coca-Cola, before it was reformulated in 1904.

In the late 1850s and early 1860s, the cocaine compound had been chemically isolated, and its chemical formula described. Scientists began to document its apparent effects, such as numbing of the tongue, dilation of pupils, and narrowing of blood vessels.

Freud, a young doctor and researcher with interests in psychiatry, neurology, and psychoactive substances, stumbled upon these findings and, given the popularity of Vin Mariani, began to immerse himself in the science of cocaine. Being a true “researcher,” he experimented on himself and on those close to him, with his wife Martha, often referred to as his cocaine companion.

He soon discovered and personally experienced the stimulant and anesthetic properties of cocaine, some of which had already been noted, though without notoriety, in medical journals.

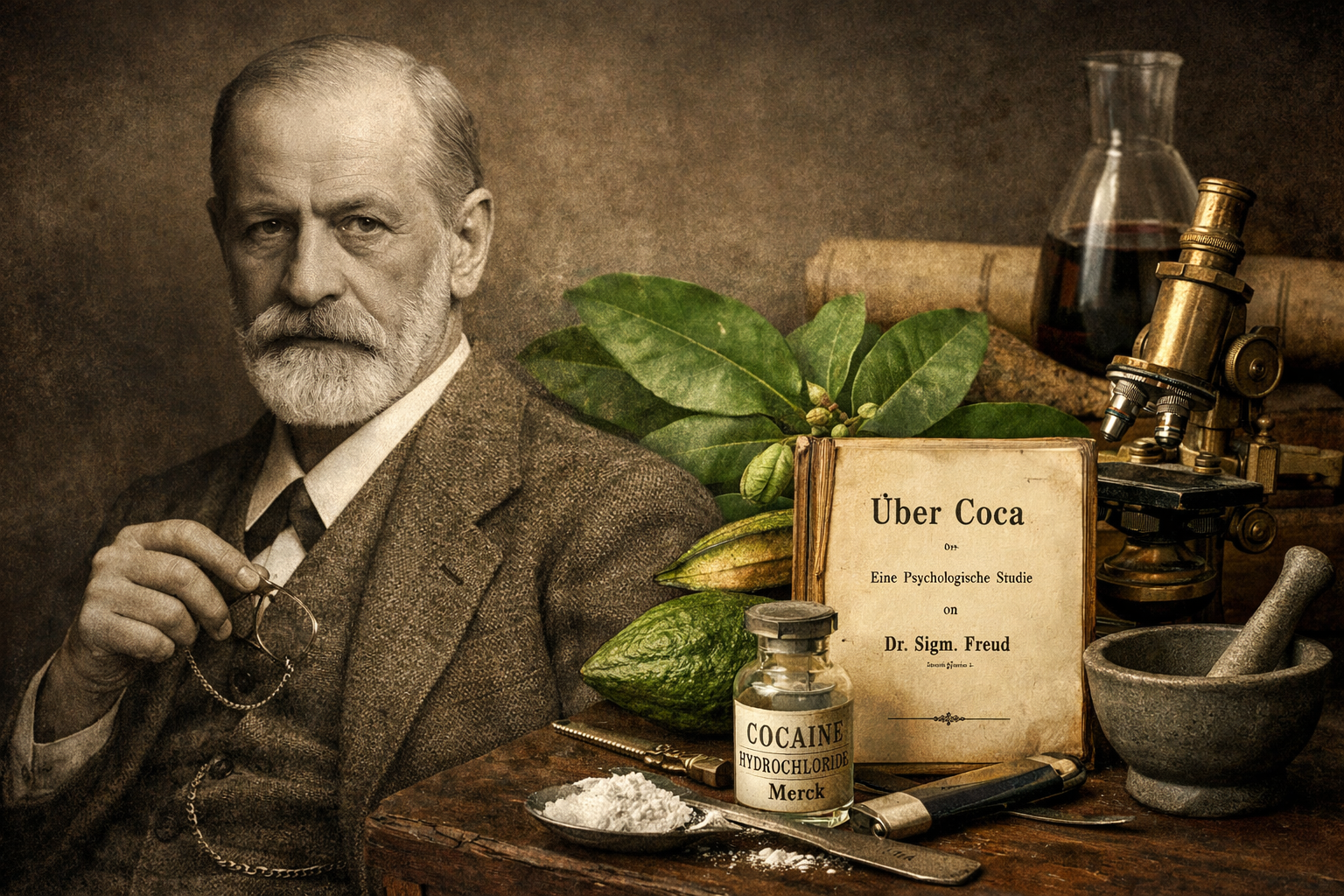

Within a year, he published a 70-page work on the benefits of cocaine use titled Über Coca. At the time, Vienna was not only the center of medicine but also a driver of Europe’s intellectual life. He deliberately titled the work “coca” rather than “cocaine,” presenting it as a review of a plant rather than the promotion of a new drug, though in reality the distinction was blurred.

A researcher making proclamations about coca or cocaine from Vienna was a significant event, and the publication took the scientific world by storm. It contributed to cocaine’s moral legitimacy and cultural acceptability. After all, if doctors said it was good, it must be.

With his interests rooted in psychiatry and neurology, Freud focused on cocaine’s effects on depression and fatigue and claimed it could cure morphine addiction, which was a major problem at the time, particularly given war-related injuries and the widespread medical use of morphine. He recognized that cocaine might have other properties, including anesthetic ones, but did not pursue them, instead remaining focused on his primary interests.

A friend, colleague, and ophthalmologist at the same university, Dr. Karl Koller, was introduced to cocaine. Having read Freud’s publication and worked under his tutelage to understand its effects, Koller chose instead to focus on cocaine’s action on the eye.

In a remarkable one-hour experiment at the Institute of Anatomy, involving only a few particles of cocaine, distilled water, and a frog, they were able to completely anesthetize one of the frog’s eyes. They repeated the experiment on a rabbit, then a dog, and finally on each other, with striking results. Both Koller and Freud had used cocaine before, but neither had anticipated this revolutionary discovery.

With scientists from an eminent university in a city synonymous with science advocating for cocaine’s effects, it soon became ubiquitous and used for nearly everything. Pharmacy counters dispensed vitality drinks, lozenges for singers, solutions for dental, eye, and ear procedures, drops for teething babies, cures for headaches and anxiety, and purported treatments for addiction to alcohol and morphine, among many others. While these discoveries did not mark the beginning of a cocaine mass market, they had a profound impact.

However, within three short years, cocaine, the miracle substance so widely touted and freely used and administered by Freud, began to reveal its darker side. Those using it for depression experienced severe rebound symptoms, often worse than before, with paranoia and hallucinations becoming increasingly common.

This ended tragically for Freud when his close friend Dr. Fleischl-Marxow, whom he had been treating for morphine addiction, developed cocaine-induced psychosis. This was at least fifty years before the first antipsychotic medication was ever produced. His friend died a few years later, addicted to morphine, cocaine, and suffering from psychosis, which abruptly ended Freud’s public involvement with cocaine.

“My studies with cocaine ended prematurely, and I would have to be content predicting the novel uses that would be discovered for this drug,” Freud later wrote in his memoirs. Had he taken a deeper interest in ophthalmology or surgery, he might have been credited with the discovery of local anesthesia, having laid much of the groundwork, popularized the subject, and strongly advocated for its experimentation and use.

The father of psychoanalysis, widely acknowledged for transforming the management of mental illness, advancing our understanding of human behavior, and illuminating the influence of childhood experience on adult life, was also, surprisingly, one of the earliest and most influential medical advocates for cocaine use and participated in promoting the early cocaine epidemic.

This makes Freud a morally complex, almost antiheroic figure in the history of medicine, one who continues to be celebrated and criticized in equal measure.